Having read your recent article in the Molesey Matters magazine I thought you could mention the next stage to the solution. Recently, whilst on a cruise down the Thames with the MTYC, I noticed several large construction sites along the river bank in London When I enquired what they were it seems that this is the upgrade to the sewer system, the scale of which is astounding. I perhaps look forward to the next issue of Molesey Matters with a corresponding article.

Best regards Geoff Lulham.

Thank you, Geoff. So here you go, and first a recap.

For centuries, the Thames has been used as a conduit for the removal of the city’s waste, and in the hot summer of 1858, a decision was finally made to rid the river of its burden. The smell of the Thames had gotten so bad that curtains hanging in the Palace of Westminster had to be soaked in lime chloride to overcome it. Newspapers of the time (and today’s historians) dubbed the summer of 1858 the ‘Great Stink’. Compelled ‘by the force of sheer stench’, Parliamentarians passed a bill into law to have the problem fixed.

The result as laid out in last month’s issue is a magnificent, 1,100-mile network of sewers comprised of more than 300 million bricks, designed by visionary engineer, Sir Joseph Bazalgette. In 1858, London was home to two million people. Bazalgette had the foresight to build his sewer system for a population twice that size, but the Victorian sewerage network simply cannot keep up with the demands of 21st Century London and need future-proofing Today, the number of people living in the capital is approaching nine million, a figure that continues to rise. So, while the sewers remain in excellent condition, they lack the capacity to meet the demands of modern-day London. As a result, millions of tonnes of raw, untreated sewage overflow.

By 2031, there will be 10 million people living in London. To cope with this increase, it is estimated that at least 600,000 new homes are needed. In order that these homes can be built the sewerage network, which is already under severe pressure, needs to be upgraded. The effect on the river’s fish, birds and aquatic mammals is profound. Ammonia found in sewage harms many of the Thames’s inhabitants, while the bacteria that feed on the sewage deplete the river of oxygen, suffocating many of its fish. This is simply unacceptable for the world’s greatest city.

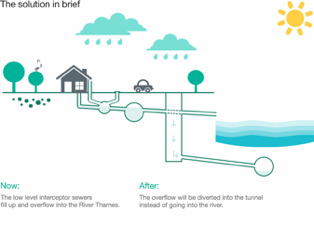

Tideway is upgrading London’s sewer system to cope with its growing population. The 25km tunnel will intercept, store and ultimately transfer sewage waste away from the River Thames. Starting in Acton, west London, the tunnel (the Thames Tideway Tunnel), will travel through the heart of London at depths of between 30 and 60 metres, using gravity to transfer waste eastwards.

In terms of timeline, preliminary construction and tunnelling is under way, with the system planned for a 2022 finish.

Who is paying?

Thames Water’s 15 million wastewater customers will pay for the Thames Tideway Tunnel through their bills. Once completed, Thames Water will operate the tunnel as an integral part of the London sewerage network, while Tideway will be responsible for its day-to-day maintenance. Thames Water’s wastewater customers will pay for the Thames Tideway Tunnel through their bills, with the process for setting customer bills determined by Ofwat. Current average annual household bills already include £13 for the tunnel and this will eventually rise to no more than £25 a year, before inflation. Molesey Matters would be interested in any views/comments. Simply email me at the address below.